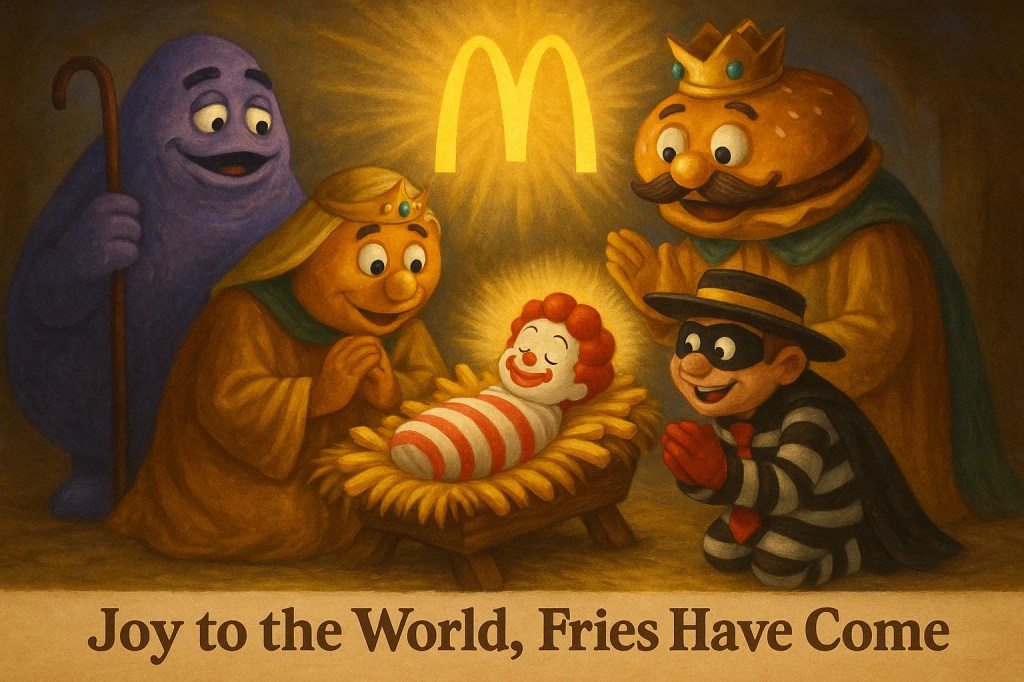

Chicago, IL – McDonald’s has found itself at the center of a holiday controversy after releasing a Christmas card that reimagines the Nativity scene with its iconic mascots. The image shows Ronald McDonald as the baby Jesus lying in a manger made of golden fries, surrounded by a fast-food retinue of familiar faces. Grimace appears as a shepherd, the Hamburglar kneels by the manger with his trademark grin, and Mayor McCheese watches over the baby like a curious monarch. Above them, a soft golden light radiates from a glowing McDonald’s “M,” standing in for the star of Bethlehem. The tagline printed beneath the scene reads, “Joy to the World, Fries Have Come.”

The card, which was reportedly intended only for internal use, began circulating online after a franchise owner shared it on social media. Within hours it went viral, provoking reactions ranging from disbelief to outrage. Faith-based organizations swiftly condemned the imagery. Reverend James Caldwell of the National Council of Churches called the depiction “a blatant trivialization of one of the holiest moments in Christian faith,” adding, “Turning the birth of Christ into a fast-food marketing moment is crossing a line.”

McDonald’s corporate office released a statement the following day clarifying that the artwork was “not intended for public release” and was merely “a playful internal creative concept celebrating togetherness and nostalgia.” The company emphasized that it would not appear in official advertising. But the clarification did little to slow the cultural firestorm. Critics and commentators quickly pointed out that this was hardly the first time a major brand had landed in hot water for blending marketing with religious imagery.

Nike, for example, faced backlash in 2005 when a decorative pattern on one of its sneakers was found to resemble the Arabic script for “Allah,” forcing the company to recall thousands of pairs. In 2011, Italian clothing label Benetton released a controversial campaign showing digitally manipulated photos of world leaders kissing, including an image of Pope Benedict XVI embracing a Muslim cleric. Coca-Cola, too, sparked outrage with a Christmas ad in Mexico that featured Santa Claus visiting an Indigenous community, a portrayal some critics said reinforced cultural stereotypes. Even high fashion has not escaped the pitfall; Balenciaga’s campaign featuring cathedral backdrops for luxury poses was condemned by many as an exploitation of sacred architecture for shock value.

According to Dr. Lillian Ortega, a professor of religious studies at Loyola University, these controversies reflect a deeper cultural tension between faith and commerce. “Corporations try to speak to universal values like joy, peace, and community,” she explained, “but they forget that religion isn’t just symbolism—it’s identity. Once you use those symbols to sell something, even humorously, you’ve entered a moral minefield.”

Yet amid the outrage, a different wave of reaction emerged—one tinged with nostalgia. For many viewers, the card marked the return of beloved McDonaldland characters long absent from modern marketing. Grimace, the Hamburglar, and Mayor McCheese were staples of childhood for many who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s. Seeing them reassembled, even in such a surreal tableau, triggered memories of Happy Meal toys, playgrounds, and Saturday morning commercials. “I thought it was funny,” said Marcus Dean, a collector of vintage McDonald’s memorabilia. “They’re part of our cultural folklore now. It’s absurd, but also kind of comforting.”

That sense of comfort, others argue, is precisely what makes such imagery powerful—and troubling. Cultural critic Hannah Lee described the scene as “a symptom of how branding has replaced belief.” In her view, the McDonald’s Nativity “shows that mascots have become our saints, logos our halos. We’ve traded the sacred for the marketable.”

Even art critics, who might have dismissed the piece as corporate kitsch, found themselves strangely impressed. The card’s soft lighting and painterly tone recall Renaissance depictions of the Nativity, lending it an unintended reverence. “It’s technically beautiful,” said Los Angeles gallery owner Peter Vance. “There’s irony in that. It looks like religious art because in a way it is—our new religion is consumption.”

As McDonald’s investigates how the image was released and vows to tighten its creative review process, the debate continues to ripple through social media and news outlets. For some, it is an example of tone-deaf marketing; for others, a mirror reflecting the blurred boundary between faith and commerce. Either way, the controversy highlights how deeply commercial imagery has entangled itself with cultural ritual.

As one viral comment put it, with the humor and exasperation that define the internet age:

“They’ve turned the manger into a marketing moment, and somehow, we’re all still buying fries.”